Kawasaki’s electric bike production system

By Ben Purvis

Motorcycle Journalist

21.07.2020

Kawasaki’s electric prototype, above, is the culmination of a decade-long project

Despite saying it has ‘no plans’ for an electric production bike in the near future Kawasaki has filed a patent application that explains just how it would manufacture such a machine.

The patent comes after a sudden flurry of electric activity from Kawasaki, notably the official unveiling of a decade-long electric bike development project at last year’s EICMA show in Milan, suggesting that a battery-powered Kawasaki might be closer to showrooms than the firm would have us believe.

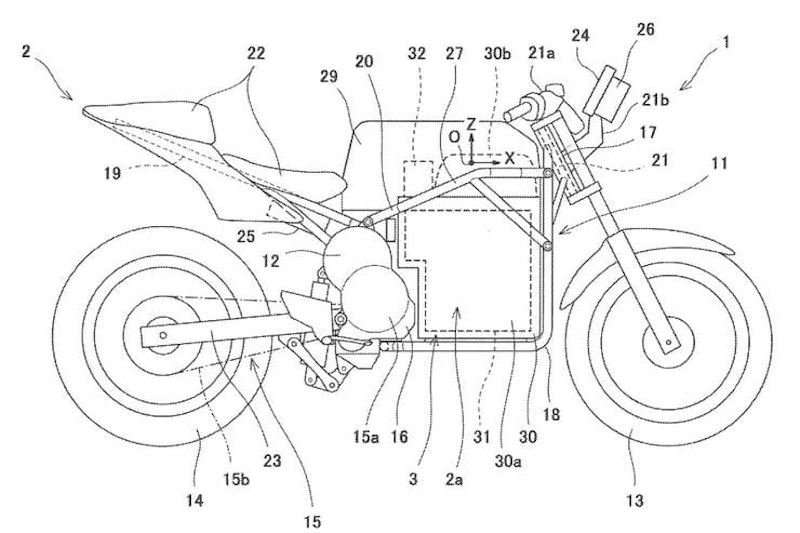

The new patent shows a variation on the design, with a different chassis but similar battery and motor

The production system is closely tied to the Kawasaki electric bike seen at EICMA and explains thinking behind its removable battery and electronics package.

While swappable batteries aren’t a new idea as a means to increase range and provide an instant ‘refuel’, that’s not what Kawasaki has in mind. Its battery pack is far too bulky to be considered swappable, and it’s also built into a unit that contains the electronic control systems. Instead, the simple removal system – achieved by removing the left hand frame rails on Kawasaki’s EICMA prototype, or by unbolting the top frame section on the design seen in this patent – is intended to allow the electronics to be easily slotted into an otherwise-complete motorcycle as a final production stage.

The battery and electronics are designed to be bolted in by dealers, not at the factory, to streamline manufacturing and shipping

It’s an idea that makes a lot of sense. During the manufacturer of a conventional, petrol-powered bike, the engine and chassis are among the first components to be mated. However, electric bikes are likely to have their electronics and batteries manufactured in a completely different facility, making it much less convenient to build the bike around them. The batteries and electronics are also relatively fragile, and if they’re incorporated early in the build process there’s a chance they’ll be damaged later on during manufacture or shipping – something that could make the bike an economic write-off if it needed to be completely disassembled to get at the battery again.

The Kawasaki idea is that the batteries and electronics will be manufactured and assembled in one factory and the mechanical parts of the bike, including the electric motor, at another. Both elements would then be separately shipped to their final destinations, with dealers tasked with mating the two sections right before the bike is handed over to a customer.

The accelerometers and gyros used for the bike’s safety systems provide early warning of battery damage during shipping

Because the electronics are assembled with the battery pack, they can effectively be active even before the bike is put together. Kawasaki’s patent shows that the accelerometers and lean-sensors used by the bike’s ABS and traction control systems will perform double duties – working as an early-warning system for battery damage before the electronics package is even put into the bike.

So if a battery/electronics unit is dropped or tipped over during shipping, the same IMU that will later become the bike’s control system will be able to alert the dealer that the battery could be damaged before it’s put into a bike.

Kawasaki’s diagram shows the production flow of the electric bike, with electronics kept separate until the last minute

The last-minute, dealer-based assembly process is designed to be very simple; the electronics unit is positioned into place, and connected with a couple of plugs and a handful of bolts. It also means the firm could easily design multiple bikes around the same electronics package and quickly respond to changing market demands by altering production volumes of the mechanical elements without having to redesign or alter the electronics. An adventure bike and a sports bike, for instance, could easily share the same battery unit. By extension, it’s even possible to envisage a situation where customers might be able to buy the mechanical section – the frame, suspension, motor, brakes and wheels – separately. You could then have two different types of bike, but only have to pay for one battery/electronics unit, swapping it from one machine to another as required.

While a patent alone isn’t smoking gun evidence that Kawasaki is about the start making an electric bike, the fact that the firm has put this much effort into its production process and designed its electric prototype around the idea shows there’s a clear effort going on at Kawasaki to make electric bikes a profitable proposition.

Share on social media: