Magnesium shortage could hit bike production

By Ben Purvis

Motorcycle Journalist

10.12.2021

Since the COVID pandemic struck nearly two years ago the business of making motorcycles has been made tougher by a host of supply and manufacturing pitfalls and now a global magnesium shortage promises to add another hurdle.

The array of supply problems due to COVID has ranged from vastly increased shipping costs – container rates have rocketed due to increased demand, labour shortages, COVID outbreaks, port closures and a lack of containers – to a well-publicised global shortage of computer chips. That’s down to COVID lockdowns that closed manufacturing plants, rising demand for electronics due to home-working, a trade war between the US and China, droughts in Taiwan (chip-making requires water) and fires at some of the biggest chip facilities in Japan. Now we can add a shortage of magnesium to the list, pushing the cost of the raw material through the roof.

The vast majority of magnesium – more than 85% of production – comes from China, but the country’s output has been slashed to around half its normal level this year. That’s due to rising costs of coal; in September, the Yulin Municipal Government of Shaanxi Province, which oversees around 60% of China’s magnesium production, with more than 40 smelters, ordered a 50% cut in output. Magnesium smelting is more than twice as energy intensive as aluminium production, so magnesium production is particularly hard-hit.

The result, predictably, is a massive spike in the cost of magnesium. For years, the metal has cost around 15,000 Yuan per tonne ($2300, £1800), but in September it peaked at nearly 60,000 Yuan per tonne (equivalent to $9400, £7100). Now, it’s at around 40,000 Yuan ($6200, £4700) per tonne.

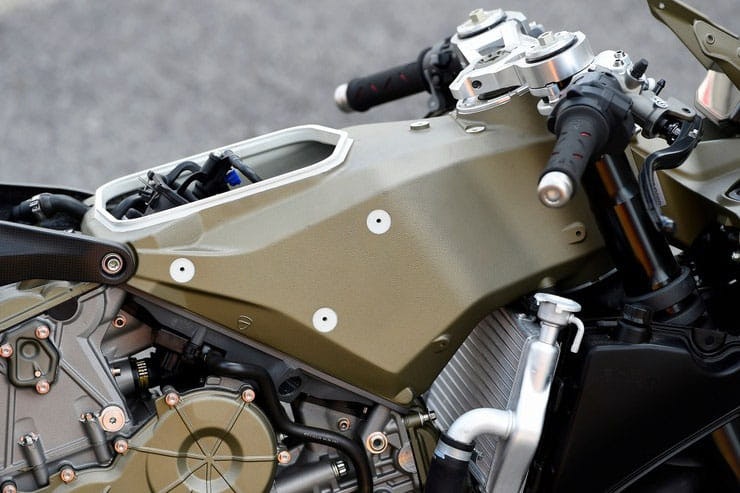

Ducati’s 1199 Superleggera was a magnesium masterpiece, using the material for its entire frame, engine covers and wheels

The automotive industry, including the motorcycle industry, is the single biggest user of magnesium. While magnesium components are usually associated with exotic machines, the metal is used as a component of aluminium alloys, increasing their strength and reducing weight. That means it appears in a vast array of aluminium alloy components, from engines to frames and wheels, on bikes, even if they’re not the sort of high-end models that specifically use magnesium alloy components.

While the magnesium shortage has the potential to push up costs or even slow production in the automotive and motorcycle industries, the Chinese coal supply problems that has caused the issue does appear to be easing. It was caused, in large part, by China’s own government, which imposed an import ban on Australian coal last year due to tensions over Australia backing an international inquiry into China’s role in the start of the COVID-19 pandemic. The Chinese government has also been trying to reduce the country’s carbon emissions by enforcing limits on coal use but has pushed to increase the country’s own coal production and looked to other sources, like Indonesia, for imported coal to replace the lost Australian supply. Magnesium production in Shaanxi has started to rise again recently, easing some of the fears of a shortage, but still remains well below normal levels.

Share on social media: