The life and times of the Yamaha YZF-R1

BikeSocial Road Tester

31.01.2018

Simon Hargreaves has ridden all seven R1 iterations on road and track; here, he ruminates on its history, and on which to buy for track days, which to commute on, which to bubble-wrap and cherish, which is best for touring, which to avoid like the plague, and nominates his favourite R1.

YZF-R1: fit to be an icon?

Every decade has its sportsbike icons; the bikes that rise above the swirling tide of hyped new models, taking on a life of their own to embody the feelings and passions of the day. Recent history’s list of such bikes isn’t long, and makes one hell of a garage: the 1960s had the Bonneville and Commando, the 70s had the Jota and the Z1. The 80s saw the GPz900R, GSX-R750 and RC30, the 1990s dawned with the FireBlade and 916, and the 00s were focussed around the GSX-R1000 K5 and Daytona 675.

But where, in this great pantheon of the sportsbiking gods, does each of Yamaha’s mighty YZF-R1 models reside? And do any of them deserve a place?

The birth of the legendary R1

According to Yamaha, the first ideas for what would become the YZF-R1 were discussed in January 1996 at the press launch of its predecessor, the YZF1000R Thunderace, at Killarney circuit in South Africa. Everyone knew the stop-gap Thunderace was not much more than a tweaked FZR1000RU EXUP motor spoon-fed into an adapted YZF750 chassis – basically, it was a bitsa; specials builders had been doing exactly the same thing for years. And everyone knew the Thunderace was still outclassed by a rapidly evolving CBR900RR FireBlade (ironically, an FZR1000RU EXUP was tested by Honda at Assen in the early 1990s to evaluate against the new FireBlade. Honda’s test riders crashed it trying to keep up with the CBR).

Yamaha’s official version of events is that even as their brand new 1002cc sportsbike was being unveiled and lauded at the track, in a separate room in the paddock a group of engineers and product planners were getting their heads together to dream up its successor, in a discussion lead by a project leader called Kunihiko Miwa – the engineer tasked with creating the next generation of Yamaha sportsbikes (he ended up with the YZF-R6 and R7 on his CV as well as the R1 and Thunderace, which is a pretty decent record). His nickname was ‘Mr No Compromise’. Catchy, eh?

Now, given almost all new models have a four or five-year development gestation, from first design concept to production, Yamaha’s official timeline of the R1’s conception in early 1996 is unfeasibly close to its late 1997 launch, less than two years later. So either Yamaha put the R1 into production in record time or, more likely, they’d waited to see how the FireBlade sold for a couple of years from 1992, then started planning the R1 some time in late 1994 or early 1995. Which is much more plausible.

But if the timing of the R1’s origin story is best taken with a savoury condiment, the detail sounds right. Miwa-san’s performance targets for the new sportsbike were 150bhp – because it was significantly more than a FireBlade – and 180kg – a figure arrived at when he stripped 18kgs off a 198kg Thunderace, including the battery, and gave it to Yamaha’s test riders to evaluate. They liked it.

But Miwa-san had another target that was arguably still more significant for the R1’s success. He knew the new bike had to be far more compact and agile than the EXUP or the ’Ace, in terms of engine dimensions, wheelbase and total width. The success of the lightweight Blade proved 1990s’ European sportsbike customers still favoured purity of purpose over compromise, and in particular showed how making big horsepower wasn’t enough on its own. The new Yamaha would have to be a radically compact package. And this presented more of a challenge.

Everything it’s stacked up to be

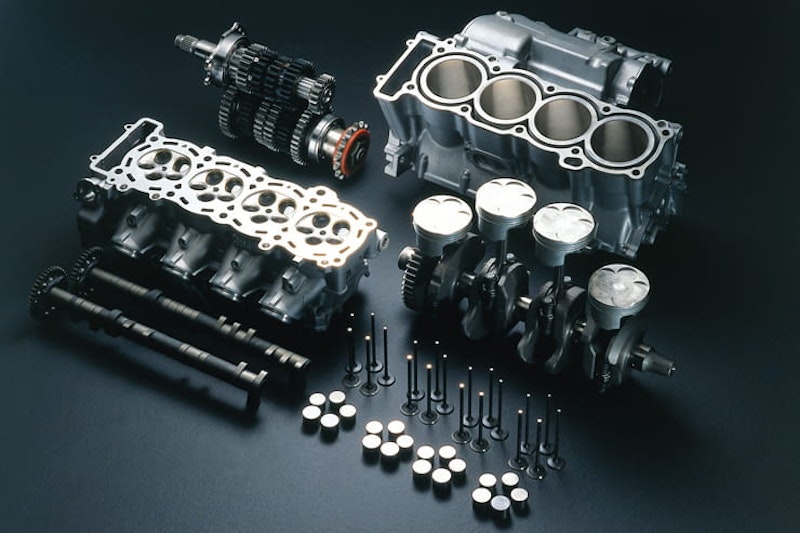

The advantage of having three contrary engineering targets – you want more power, less weight and in a smaller space? – is that advances in one tend to create opportunities in the others. For example, a weakness of Yamaha’s early five-valve Genesis motor was that, at a 40° forward slant angle, the crank centre was moved back, away from the front wheel, which had less than ideal implications for front-to-rear weight distribution. But if the engine’s transmission shafts were to be vertically stacked, raising the clutch centre behind the cylinder block and forming a triangle between crank, drive shaft and main shaft, this would negate the effect and allow the motor to be positioned for an optimal centre of gravity – but also shortening the front-to-back length of the motor. And this would be great news because it’d unlock lots of chassis design options. It’d mean the R1 could have a longer swingarm relative to its wheelbase (copying Yamaha’s YZR500 GP bike design), which is good because there’d be more room to fit suspension, more control over the chain run and associated forces, better control over traction, and greater stability. And so it proved.

But the new R1 engine wasn’t just shorter; it was narrower too – all drives came off the end of crank and plated bores were used instead of liners, saving weight and closing up the cylinders. Even so, width was reduced still further by not going overboard (sorry) on bore width: at 74mm x 58mm, the R1’s bores were narrower than the Thunderace’s, which potentially limited valve area, lowered piston speeds and may have led to lower peak power (if not less peak torque) than the older motor. But a reduction in weight (of around 9.5kg on the Thunderace) and less internal friction – including introducing holes between the cylinders to equalise under piston pumping forces (traditionally something Suzuki would bang on about in their GSX-Rs) – meant the R1 motor hung on to its EXUP-valve augmented peak power and torque figures to produce 140bhp at the back wheel – comfortably ahead of its rivals by almost 20bhp and 10bhp up on the Thunderace.

And the R1 was light too – with the engine, designed to be stiff as well light – acting as a genuine stressed frame member, it meant the actual frame itself could be lighter. The R1’s claimed weight was 177kg; the measured kerb weight was 202kg – 6kg better than the rival FireBlade, 11kg down on Kawasaki’s ZX-9R, and more power than both.

So that was how Yamaha designed the first R1. The rest, as they say...

WHICH IS THE BEST R1 FOR YOU?

THE CLASSIC R1

Gen 1: 1998 – 1999

£2500 – £15,000 + (seriously!)

Back in 1998, when not all new bikes were unanimously praised from ceiling to floor, it was easier to tell when something genuinely extraordinary had come along. And when, in 1998, the first YZF-R1 4XV did, you had three options: 1) stand outside the Yamaha dealer window and press your face against the glass, 2) buy one at the £9199 asking price and ride it, or 3) buy one and wrap it in cotton wool as an investment.

Which, do you think, would’ve been the best option?

Clearly, the right answer is 2). Because if you chose 3), today your mint 1998 R1 with zero miles would have to be worth nearly £15,500 to deliver anything close to a return on your investment. Which it won’t be (although that doesn’t stop some dealers trying; there’s a 600-mile 1998 R1 on Autotrader at the time of writing, and the dealer is asking nearly £17k!).

But even so, like any first edition of a classic, the original R1 is a special machine and most people want one because it’s a lovely thing to possess: it looks pure, purposeful and minimal, because it hails from a time before emissions regs and electrical safety aids forced all manner of gubbins onto bike engines, and bodywork wasn’t built to quite the same budget bottom line from scraps of sweet-wrapper plastic.

And if the first R1 is lovely in the garage, a fettled one – which inevitably means one with balanced carbs, correct valve clearances, working EXUP valve, serviced suspension, new tyres, working brakes, and fresh head, wheel, cush, suspension and swingarm bearings... and with a steering damper; it’s really not a long list – is still a force to be reckoned with on the road. And it’s also a pleasure to use; the riding position, radical at the time, isn’t so bad now (try the new R1 for radical), and the power delivery comes from a smoothly carbureted, low-down piledriver of a motor. Handling can be a bit wayward, especially front end stability (and exacerbated by bolloxed suspension, which is why you need it refreshing). Even new, the R1 was prone to tankslap – but unlike, say, a bad Suzuki TL1000S or Kawasaki’s KR-1S, the R1 would nod gently before kicking off, giving the rider plenty of warning it was exceeding design parameters. And it’s not worth ignoring just for that minor indiscretion.

But, like all classics, the biggest problem with owning an original R1 is actually riding it without feeling guilty. You can’t rack up the miles on one, or rag it the way Miwa-san intended, because... it’s too good to spoil.

THE SMART R1

Gen 2: 2000 – 2001

Start: £2350 – £5000

The second generation R1 featured a round of updates – as was the case with the original 1992 Blade and even the first GSX-R750F in 1985, it seems like manufacturers get the willies with second-generation models and back off a little from the purity of the first bike. Or maybe they just have a bit more time to get them right. Either way, the Y2K R1 was more user-friendly and a more settled machine, less prone to the odd tankslap with a longer swingarm and wheelbase, headstock and frame reinforcing and revamped suspension settings (like, 0.1mm thinner fork springs!). It also got minor modifications to brakes, riding position (lower bars, lower tank, more rearward rearsets), and sharper, pointy bodywork with a claimed 3% less drag. The engine got lots of minor improvements, with new cam timing, tighter valve clearances, smoother transmission shifting, carb, ignition and EXUP valve tuning, plus weight loss from the cylinder head, starter motor, oil filter, CDI box and the new titanium end can. Power and torque remained the same, but the R1’s weight dropped by 2kg to 175kg.

The reason this model is the smart buy is because second gen models don’t attract the same kind of ‘fashion tax’ premium added to first gen bike – so you’re effectively getting a slightly more refined, better behaved, no less intense but significantly cheaper version of the same thing.

THE R1 TO GET

Gen 3: 2002 – 2003 (FI)

Start: £2500 – £5000

In 2002 the R1 got another overhaul. The R1’s father, Kunihiko Miwa, handed over the reigns of the YZF-R1 5PW to new project leader, Yoshikazu Koike, who said: “Our biggest challenge was how to keep the great qualities of the R1 while continuing its evolution to a new level. Our aim was creating a machine that responds directly to the rider’s actions and a very high level of cornering performance.” Ah, good. Make it better, then.

That meant a new, stiffer, lighter frame (the first to be ‘shrink-wrapped’ vacuum die-cast), a detachable subframe, a stiffer, asymmetrical swingarm, new, stiffer suspension with less travel, repositioned engine and rider for higher c of g and shaper steering response, as well as new, shaper styling.

The engine got an ingenious new hybrid fuelling system, which used fuel injectors to squirt petrol into the intakes, but controlled the air flow using conventional CV-style carb slides – a great idea for minimising fuel injection snatch; a problem that was plaguing Yamaha’s M1 MotoGP bike of the time. The engine’s fundamental architecture remained the same, but another round of weight loss and fine tuning through the intake, engine and exhaust system boosted power to a claimed 152bhp.

The reason this is the best R1 is because it’s the last of the original engine spec, benefiting from all the old-school guff about linear power and bottom end response – but also with the novel combination of fuel injection and CV carbs smoothing out the fuelling. And although the styling is advancing, it’s still not close to peak disjointed multiple plastic panel nightmare. Plus the bike still has a proper end can (not underseat). The 5PW R1 is the one to get.

THE DAILY R1

Gen 4: 2004 – 2006

Start: £3500 – £5750

2004 saw the R1’s first complete overhaul. An new motor with wider bores and shorter stroke raised revs and helped push peak power up to a claimed 172bhp which, combined with a claimed 172kg dry weight, meant a 1:1 power to weight ratio. Although having said that, Yamaha were soon to be caught out being flexible with the truth about the peak rpm claims for their YZF-R6, so any numbers they published around this time need to be treated with caution.

But, either way, the new engine was significantly more powerful than its predecessor – also assisted, for the first time on the R1, by ram-air pressurising the airbox (which is a surprise when you consider Yamaha were the first to slant the engine in the frame, in 1985’s FZ750, which moved the air-box into the ideal position for ram-air charging, just behind the headstock; wonder what too them so long to utilise it?). For 2004 the R1 went fully fuel injected, ending the experiment with hybrid FI/CV carbs – presumably engineers solved the snatch issue. Lucky them.

And frame ran a straighter path to the new ‘upside down’ swingarm, with the engine no longer a stressed member and, freed from its chassis duties, could now be lightened. Suspension and brakes were revised again, and the most obvious styling detail was a move to the then fashionable underseat exhaust cans, which offered several advantages; it theoretically centralised mass (never really convinced of that), and it also meant tuning the right exhaust length wasn’t a problem – and, best of all, it was cheaper to make because exhaust cans could be cheap and ugly; you couldn’t see them so it didn’t matter. On the downside, it became tricky to strap luggage on and pillions got hot bums. But don’t they always.

In 2006 Yamaha lengthened the R1’s wheelbase, and added an SP version to the R1 line-up, with a slipper clutch, Öhlins forks and shock and forged aluminium Marchesini wheels. It’s very pretty, but nowhere near worth £14,000, or £5000 extra over the stock R1 in 2006.

But the reason the stock 2004-2006 R1 is the best day-to-day R1 is simple: it was relatively unpopular at the time (against hotter rivals) so prices were depressed from the start. And they still not great today; plus, the bike isn’t viewed as a classic model so lacks any of the status premium – and that also means you’ll slightly less worried about the bike when it rains on it as you’re commuting to the office and back in early February. This is an R1 you could care the least about, and not feel too guilty.

THE TRACK R1

Gen 5: 2007 – 2008

Start: £4000 – £6250

See ya later, Genesis. No, not the prog legends, but Yamaha’s five-valve head. Since the FZ750 in 1985, Yamaha had stuck with three intake, two exhaust valves per cylinder while everyone else used two of each. Part for of the rationale for using five valves in the first place was to help encourage mixture swirl as the charge entered the combustion chamber, improving the burn and overall engine efficiency. But it was known all along that five valves added complexity (and weight) but, more importantly, limited gas flow; five valves crowded into a combustion chamber roof don’t give as much valve area as four valves. At some point in the pursuit of power, they would have to go. And that point was 2007.

To make up for it, Yamaha made the remaining eight exhaust valves from titanium. They also introduced a couple of new technologies: YCC-T (Yamaha Chip Control Throttle), a kind of semi-fly-by-wire system in which the throttle turns a cable, which in turn actuates a potentiometer and tells the bike’s ECU what to do with the throttle valves, and YCC-I, or variable length intake trumpets to tune the intake length depending on engine revs. The 2007 bike also got the previous year’s SP slipper clutch, yet another new frame and swimgarm, and six-pot calipers. And another restyle, too – but the exhaust was still under the seat. In 2007, on the R1’s ninth birthday (eh?), Yamaha also reintroduced a red and white colour scheme, similar to the original 1998 bike – and, like the first bike, it’s very pretty.

The 2007-2008 R1’s make cracking track bikes because a) 2007 was the year Noriyuki Haga’s R1 was pipped to the World Superbike title by James Toseland, by a mere two points, and b) because it was produced just prior to the credit crunch – and when the new, 2009 crossplane crank R1 was revealed, dealers were discounting 2008 R1s by up to several thousand pounds in an effort to shift them. This was amazing value, and so many riders could afford to run the R1 as a second bike purely as a track machine – which is how many ended up being used. You need to check where it’s been before you buy; but it’s still a cracking track machine either way.

THE LEAST LOVED R1

Gen 6: 2009 – 2014

£5500 – £8500

How long have you got? Pull up a seat. The 2009 R1 featured a novel idea borrowed from the MotoGP M1 that powered Rossi to his maiden title on his debut year on the Yamaha in 2004. Developed for the race bike legendary Yamaha race engineer Masao Furusawa, the idea of a crossplane crank layout in an inline four was a radical solution to a big problem. On a conventional inline four crank at rest, the crankpins (rods and pistons) are arranged in a two up, two down fashion. This means when the engine is running, it’s pretty much balanced and feels smooth. On a crossplane crank, the crankpins are spaced at 90° intervals, which (in a four) is unbalanced. So why do it? Because it has, at least on the race bike, an important attribute. In a normal inline four, the two-up, two-down piston motion is stop-start and uneven (non-sinusoidal, if you must know) – so although the engine feels smooth, the flow of torque arriving at the rear wheel is effectively staggered and non-linear. With a crossplane layout, the piston movement is such that the flow of torque to the wheel is much more linear, or less ‘noisy’. Or, to put it another way, what a crossplane inline four does is, almost literally, imitate the firing intervals and torque delivery of a V4.

In the rarefied atmosphere around Valentino Rossi’s throttle control when he’s on the edge of tyre grip mid-corner, mid-race, this means he gets a more direct, controllable connection between his brain and the rear tyre. Good for him.

Back in the real world of ham-fisted idiots, Yamaha’s decision to transfer Rossi tech to the road didn’t immediately pay off; the associated reinforcement and balancing of the new engine meant it was relatively wide and heavy – which made the new R1 a cumbersome, awkward beast, especially when compared to its lithe, quick-steering litre bike rivals. The motor sounded great and felt lovely – it was just a bit of a bus.

Worse, the bike was excessively sportily arranged, with a very wrist-heavy riding position. The new motor was aggressively tuned too, with a very responsive throttle (even with newly added engine modes to choose from). And, finally, Yamaha painted the frame a deep shade of pink.

Compounding all that lot was the newly arrived credit crunch, wiping out any enthusiasm for buying new bikes from Japan, especially when a global rearrangement of exchange rates added a couple of grand to the price overnight. Not even the addition of traction control and minor fuelling refinements in 2012 made much difference – the arse had fallen out the sportsbike market big time and it would take something special to get it back.

Not that should bother you on the used market today – but, even now, there are much better R1s to choose from than the first gen crossplane crank R1. Whatever Valentino says.

THE ULTIMATE R1

Gen 7: 2015 – 2017

£10,500 – £19,800

In 2015 the second generation crossplane R1 – effectively the comeback R1 – started from scratch. Yamaha made no bones about it: “This new machine is a purely focused sport bike that has been developed primarily for the racetrack.” Everything was new; nothing was borrowed from the older bike.

The new engine went wider still on its bores and to permit more revs and power – which is now up to a claimed 198bhp – but the engine was also significantly lighter and more compact than the previous bike, thanks in part to a new design of crank and balancer, returning the R1 to its super-agile state. Dry weight was 179kg, helped by titanium con rods, magnesium wheels and subframe. But aside from the completely new styling chassis and engine, the R1 got a full suite of electronic aids derived from MotoGP, informed by a host of sensors feeding into a six-axis inertial control unit – with functions including intelligent slide control as well as traction control, wheelie control, launch control, cornering ABS, quickshifter; the 2015 R1 featured the lot.

Well, not quite – alongside the base R1, the R1M added Öhlins semi-active suspension carbon bodywork and a race-spec data link to the mix.

The second gen R1 banished the woes of the first crossplane bike, transforming the set-up into a world-class track tool capable of mixing it with the best of the class. It’s a demanding and uncompromising machine, and on the road it’s hard to enjoy riding it until you’re dipping into truly absurd levels of performance – other litre bikes are more civilised. But it’s then the Yamaha really comes alive; on song, it’s new crossplane motor is one of the most addictive, soulful and plain beguiling engines ever built.

Share on social media: