Speed limiters and black boxes on cars by 2022. Are bikes next?

By Ben Purvis

Motorcycle Journalist

03.07.2019

In March this year the European Union institutions reached a provisional agreement to make a host of new safety features mandatory in all new cars from May 2022 including ‘intelligent’ speed limiters and aircraft-style ‘black boxes’. And while motorcycles have yet to be incorporated into the planned legislation it’s likely that bikes will eventually wander into the rule-makers’ crosshairs.

Safety technologies that make their debut on cars usually filter down to motorcycles within a few years, and where they’re proved to be successful it’s sure that given time they’ll become mandatory, just as happened with ABS brakes. So instead of sniggering at the misfortunes of our four-wheeled friends, we need to take a close interest; what happens to them may well befall us in the future.

What technologies are we talking about?

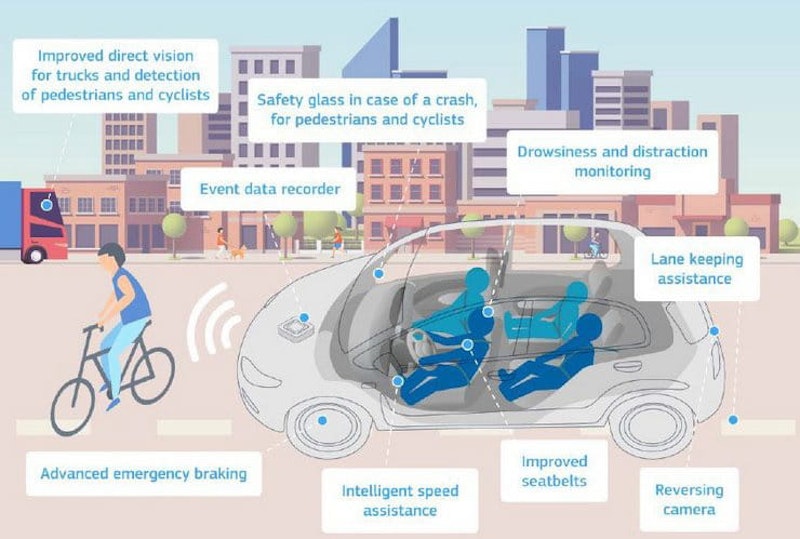

Speed limiters and ‘black boxes’ (event data recorders) have garnered most of the headlines since the EU provisionally rubber-stamped the new rules in March, but the full list of technologies that are to be mandated is rather longer.

The full list of enforced technology includes:

Advanced Emergency Braking Systems (AEBS). These use radar, laser or camera-based technology to pre-empt a collision, warn the driver and automatically apply the brakes to prevent or mitigate an accident. These systems are already mandatory on new trucks and busses and are becoming increasingly common in cars. They’re also on the horizon for bikes, with Ducati, KTM and Bosch all developing radar-based adaptive cruise-control and collision-warning systems and the first production models using them expected to be on sale next year.

Alcohol interlock installation facilitation. While the EU is stopping short of making all drivers have to take a breath test before starting their cars, the new rules will force manufacturers to make it easy to fit an ‘alcohol interlock’. These are simply breathalysers tied into the vehicle’s ignition system so the car won’t start until it’s registered a clear sample. They can also be set to trigger at lower than the legal blood-alcohol limit and to require random re-testing during a journey (with a few minutes warning to give the driver a chance to pull over safely first). The systems are already in use many countries, particularly for professional drivers or those with previous drink-driving convictions.

Distraction recognition and prevention systems. Cars are getting increasingly automated – and more so with the addition of the mandatory new safety systems – so car makers are being asked to add systems that ensure drivers are paying attention even though there’s less for them to actually do. These systems usually monitor steering, but can also incorporate cameras pointed at the driver to see if their eyes are on the road.

Event Data Recorders. The so-called ‘black boxes’ inspired by longstanding aircraft practice, these will record data such as speed, braking and steering. In the event of an accident, the boxes are triggered to save a few minutes before, during and after the impact. They’re sure to help police prove who was at fault in an accident, but as with so much ‘Big Brother’ technology, there’s a conflict between the ‘if you’ve done nothing wrong, you’ll have nothing to hide’ argument and the uneasy feeling of being constantly under surveillance.

Emergency Braking Display. Nothing too nefarious here – just brake lights that will flash rapidly when drivers are hard on the anchors or ABS is activated.

Head impact zone enlargement. This isn’t going to change bikes but it could be beneficial for motorcyclists – it’s a move to increase the area of cars designed to mitigate injuries to pedestrians and cyclists if they’re hit by a car. Although motorcyclists aren’t specifically mentioned, as we’re similarly soft and squishy it’s likely to be a benefit to us in some car-vs-motorcycle accidents.

Intelligent Speed Assistance. This is the big headline-maker – despite its ‘assistance’ branding, it’s a speed limiter that effectively means it will be impossible to absent-mindedly drift over the speed limit. Drivers will be able to override the systems by pushing harder on the throttle, but there won’t be an off switch and the EU is already investigating the idea of a second-generation of system that can’t be overridden. More on this below…

Lane Keeping Assist. Already used on many new cars, lane keeping assist keeps an eye on lane markings and help steer the car if the driver accidentally begins to drift across it. It still needs to be switched on manually, though, so it doesn’t appear that drivers will be forced to use it.

Reversing cameras. Not something that is ever likely to carry over to motorcycles, but they might stop some numpty from backing into your pride and joy one day.

Tyre pressure monitors. Already mandatory on new cars, these are being extended to vans, trucks and busses as well. Since an increasing number of bikes are also fitted with the systems they’re likely to become mandatory on two wheelers sooner or later, too.

Vulnerable Road User Detection and Warning on front and side. Only being mandated for trucks and busses. Although developed with pedestrians and cyclists in mind, these systems could be a boon for motorcyclists as well, warning drivers when there’s someone in a front or side blind spot.

Vulnerable Road User Improved Direct Vision. Again, it’s only for busses and trucks, but this rule is intended to change their design to increase the driver’s field of vision so it’s easier for them to see pedestrians, cyclists or motorcyclists when they’re near the cab.

Speed limiters: How do they work and do we need to worry about them?

There’s no doubt that of all the technologies being mandated for future cars – and which could filter down to bikes after that – speed limiters are the ones that sound most like an invasive infringement of liberty.

From a logical and legal standpoint, it’s hard to make a persuasive argument against them; we’re not supposed to break the speed limits and while you’re below the limit they do nothing. But do you feel comfortable with the idea of having the very ability to break the limit taken away?

According to the proposals rubber stamped by the EU, the limiters can be overridden but not switched off. The proposal says: “it shall be possible for the driver to feel through the accelerator pedal that the applicable speed limit is reached or exceeded” but also that “it shall be possible for the driver to override the system’s prompted vehicle speed smoothly through normal operation of the accelerator pedal.”

They’ll use a combination of GPS and a central map of speed limits to monitor where you are and what the speed limit is, while the systems can also use cameras to ‘watch’ for road signs with cameras. Several cars already on sale right now have switchable ‘Intelligent Speed Assist’ systems, so they’re a proven technology. The difference is, of course, that the current systems are a true ‘driver assist’ system that can be turned off at will, according to the EU’s proposal at the moment “it shall not be possible to switch off or supress” the mandatory systems.

There are valid reasons for the systems to be overridden. The European Transport Safety Council, which pushed for the adoption of Intelligent Speed Assist (albeit preferring the ability to switch them off altogether), gives the example of a situation when a car is overtaking a lorry when he passes a change in speed limit. It said: “In this case, the driver could temporarily override the lower speed limit and complete the manoeuvre at a higher speed by depressing the accelerator down hard to signal to the system that the limiter should be temporarily disabled.”

The override also helps shift the onus for speed control to the driver. If, for instance, there’s a temporary or variable speed limit in place, or the car’s map or speed limits or the central database speed limit information isn’t right, it will remain the driver’s responsibility.

The European Automobile Manufacturers’ Association (ACEA) has already expressed concerns. In a November 2018 document entitled ‘Why ISA cannot become mandatory today’ it said: “In practice, ISA systems still show too many false warnings due to incorrect or outdated speed-limit information. For example, because road signs are not harmonised across Europe. Digital maps are also not fully populated with speed limit information for all roads, and data are not always updated. Moreover, camera-based systems cannot anticipate all scenarios, such as when traffic signs are covered up.”

It suggested “ISA systems should be introduced gradually in cars to provide enough time to update our infrastructure, including new solutions for providing reliable information to the vehicle.”

Unlike speed cameras, it’s hard to make an argument that these systems are some sort of surreptitious way of boosting coffers. If anything, governments are going to suffer from a massive drop in fines from speeding offences. But despite the fact that the impetus behind them appears to be a genuine desire to cut accidents – Intelligent Speed Assist is a central component of the EU’s ‘Vision Zero’ concept which has the eventual aim of eliminating road deaths – it’s hard to shake the feeling that it’s an infringement of freedom.

That feeling may get stronger still if the EU’s full plans come to fruition: in a working document released in June 2019 the European Commission said that it “may consider for the future the feasibility and acceptability of non-overridable Intelligent Speed Assistance.”

What’s the likelihood that bikes will also be affected by speed limiters?

At the moment there’s no discussion at European level about fitting motorcycles with Intelligent Speed Assist – but it’s hard to imagine that we won’t get dragged into the conversation at some stage in the next few years.

Right now, bikes are less well suited to adopt the technology. While a vast number of cars already have cruise control and GPS as well as camera-based setups to recognise road signs, and such systems are available ‘off-the-shelf’ to car manufacturers, there’s little equivalent on two wheels. Yet.

Technological trickle-down means that the building blocks of the system are likely to be adopted on bikes over the next few years, though. Cruise control is becoming much more common, and adaptive cruise control – able to monitor and keep pace with the vehicle ahead – is set to reach production on at least one model in 2020. GPS systems are also incorporated into a growing number of two-wheelers, with costs plummeting, so there are few technological hurdles to adding intelligent speed limiters to motorcycles.

Initially, only new cars made from 2022 onwards will need the system, but that means by 2030 the vast majority of vehicles on the road will be speed-limited. It’s inevitable, therefore, that the pressure to apply the same rules to two wheelers will get increasingly strong.

The EU hopes that by 2030 its rules are going to see road deaths and serious injuries halved compared to the level in 2020, and by 2050 the aim is to have ‘almost zero’ deaths or serious injuries on the roads. Those targets aren’t going to be met unless it turns its attention to motorcycles at some stage, so we should be prepared to see it happen.

Road policing: The hidden casualty of intelligent speed assist?

Although it’s too early to try to predict all the impacts of the EU’s new technology-focussed road safety plans, the huge reliance on ‘driver assistance’ technology – whether it’s speed limiters, lane assist, anti-distraction tech or drink-driving prevention – means there’s going to be an ever-decreasing need for actual police monitoring our roads in years to come. Throw in ‘black box’ tattletales that will finger the responsible party in a road crash and the increased ability to track and monitor road users remotely and it’s not impossible to see a point at which the need for regular police patrols will effectively evaporate.

Doesn’t Brexit mean this is all somebody else’s problem?

While a lot of the more Orwellian elements of the planned scheme might sound like exactly the sort of thing that has pushed people towards voting for Brexit, in fact it’s unlikely to make any difference whether we leave the EU by October 31 or not.

It’s already been made clear that our vehicle legislation is going to remain aligned with the EU even after we’ve left, and it makes sense to do so. Many other parts of the world are also increasingly bringing their legislation into line with European standards, and to have a different set of rules for construction and use of vehicles in this country would make little sense and face a vast amount of opposition from the car industry.

The ‘glass half full’ view

It’s easy to be drawn to the idea that speed limiters and prying ‘black boxes’ amount to an infringement of liberty, but it’s vital to remember that the laws are aimed at a majority of road users who have zero passion or interest in their mode of transport.

They don’t care how their cars work, have no desire to improve their driving abilities and are largely oblivious to the people they share the roads with. Computers, radars and all the other technology being incorporated into the cars of the future will help stop them from smashing into each other. But the EU’s technology-based solutions to reducing road accidents are aimed at addressing the shortfalls of the masses, not crushing the tiny minority who take an interest in their cars and driving skills.

The proportions are reversed when it comes to motorcyclists. The majority are enthusiasts, taking pride in their awareness and ability and always looking to improve their riding skills. If the technical changes being implemented on new cars in 2022 work as planned, they’ll help reduce the unpredictable behaviour of bad or uninterested drivers and, for a few years at least we’ll have a situation where our bikes – as yet not included in the EU’s plans for ‘assistance’ systems – will truly offer a level of freedom that car users will be prevented from enjoying.

Keen car drivers will look on in envy, and surely a lot of who’ve teetered on the edge of switching to two wheels will be driven to take the plunge. Yes, it’s likely that the spectre of speed limiters and black boxes will loom over motorcycles in a decade’s time, but by then our ranks will have been swollen. Perhaps by using the organic computers between our ears and the visual sensors mounted on the fronts of our faces, we can show that we’re able to match or outperform the mechanical equivalents being foisted onto future cars, and the law-makers will be persuaded to look elsewhere for their technological methods to save us from ourselves.

Share on social media: