How it works: the motorcycle clutch

By Gary Baldwin

Director of Rapid Training

12.03.2018

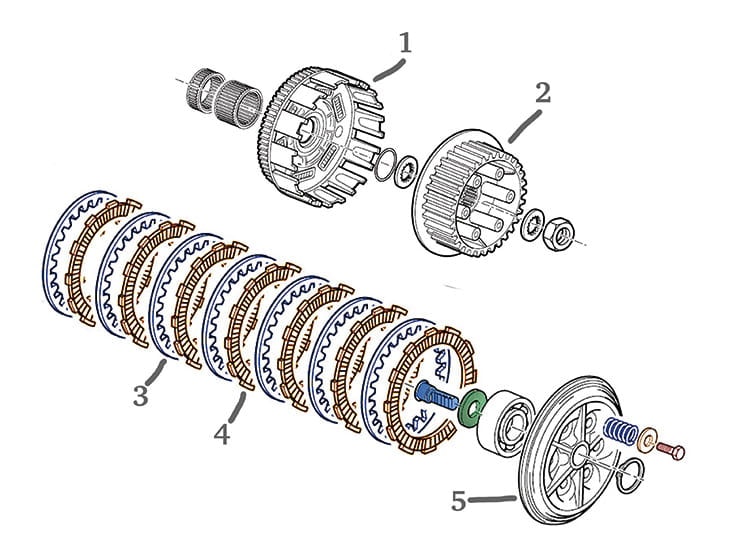

Clutch housing. This is what gets turned by the crank. The tabs from the friction plates locate in the gaps.

The clutch is one of those devices that we use all the time but barely think about. In theory it’s so simple - it’s just a method of allowing the rider to disengage the power from the rear wheel, so the engine can spin while the bike sits still.

But in the early days of motorcycling some bikes didn’t bother with clutches and if you ever get a chance to ride one it’s worth doing. Ye Gods they’re tricky. Every start is a bump start and stopping entails either stalling, or lifting your weight off the saddle so the rear tyre can gently spin (they weren’t big on tyre traction in them days). Plus of course, there are no gears - you can’t have them without a clutch.

Most motorcycle clutches are manual (ie not in an automatic gearbox), wet (they run in oil) and multi-plate (multiple friction surfaces are used), so let’s look at those. The basic idea is that the power from the engine turns a disc shaped like a big washer with a large hole in the middle. That’s a clutch plate. If the rider wants the power to go to the back wheel they let out the clutch lever, which allows springs to push the plate onto another plate that is connected to the rear wheel via the gearbox and chain. As friction between to two plates builds up, so more power is transmitted to the rear wheel, until the plates are locked and maximum power goes from engine to tyre.

It gets complicated with bikes because space is so tight in across the frame 4-cylinder engines. If you were to have just two clutch plates, they would have to be massive to have enough surface area to create the friction necessary to transmit the power. So most bikes have multi-plate clutches.

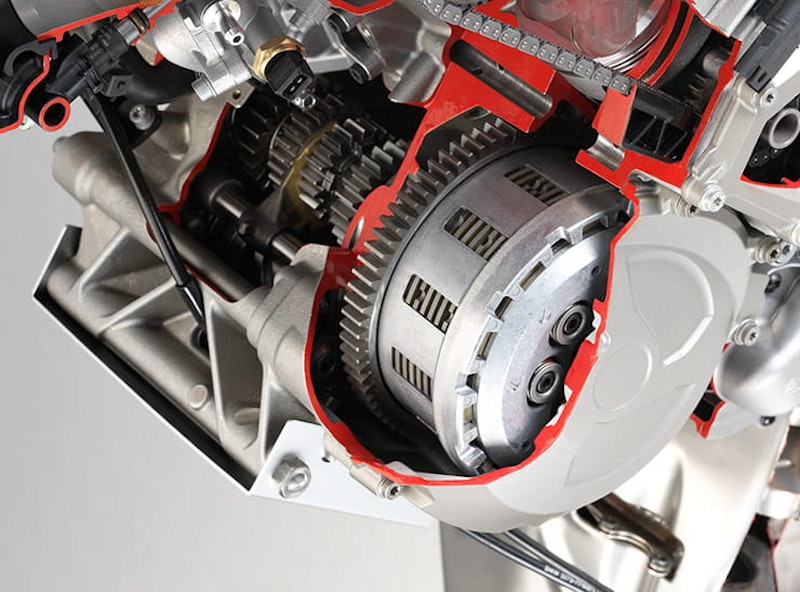

The clutch pack on a BMW S1000RR. The drive is applied to the teeth on the housing and exits stage left into the gearbox

With these, the principle is the same, but instead of two big plates, there can be over 10 smaller ones. Half of them will be connected to the crankshaft (either directly on the end of the crank, or turned by a primary drive gear), and half are connected to the gearbox input shaft. The crankshaft plates have friction material attached to their faces and use tabs on their rims to lock into the clutch housing (that’s the bit that usually gets driven by the crank). The gearbox plates are plain steel and have teeth on their inner circumference which slot onto the gearbox shaft.

The two types of plate are alternated, so that both sides of all except the end ones get used to create friction. When you release the clutch lever you release the clutch springs, which push on a plate (called a pressure plate) which evenly forces the clutch plates together.

How many clutch plates? Well, it’s a trade-off. It depends how much power you need to transmit (more power = more plates), how big the plates are (smaller = more plates), what your friction material is like (more slippy = more plates), and the strength of the clutch springs (weaker = more plates). Massive power in a compact bike can mean a heavy clutch.

Given the importance of friction in all this, it might seem odd that most clutches run in a lubricant – engine oil. The answer is that friction creates heat which can easily destroy the friction material, and oil helps prevent your clutch from burning out. Wet clutches can take a lot of abuse or last for ages or indeed both.

This is the wet clutch which has been in BMW R1200GSs since 2013. Before that it was a dry one, and you had to split the engine in two to get at it.

It also means that all the other moving parts – the bushes, bearings and the plates themselves – move smoothly. But, inevitably, even specially-designed compounds of friction material aren’t hugely efficient in oil, so more plates are needed, which means more weight. Also, all that oil sloshing about saps power. Which brings us to…

Dry clutches lose less power and their plates create more friction than wet ones, so they can be smaller and lighter too – hence their use in MotoGP bikes and decades of Ducatis. They also make that charming engine-about-to-explode clatter at tickover (the sound is all the plates rattling - it disappears when you let the clutch out). BMW twins and Moto Guzzis often use dry clutches too, but this is because the crank runs from front to rear, so there’s more room for a large car-style dry clutch.

Generally though, dry clutches on road bikes are on the way out – less durable, more noisy and they can be finickity to use when they get hot.

And as for slipper clutches, scooter automatics and Honda’s DCT? We’ll come to those another day.

Share on social media: