Hydrogen-powered electric Honda in development

By Ben Purvis

Motorcycle Journalist

09.10.2017

A new patent application from Honda reveals that the firm has been working on an electric bike that eschews batteries in favour of a NASA-style hydrogen fuel cell.

In theory, hydrogen fuel cells offer the green benefits of electric power combined with the power-density and ease of refuelling of petrol. The reality isn’t so clear-cut, but we’ll get on to that…

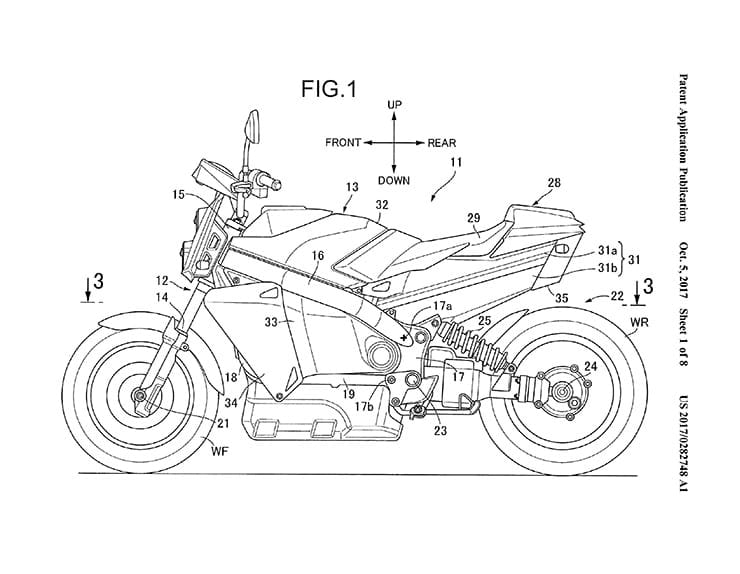

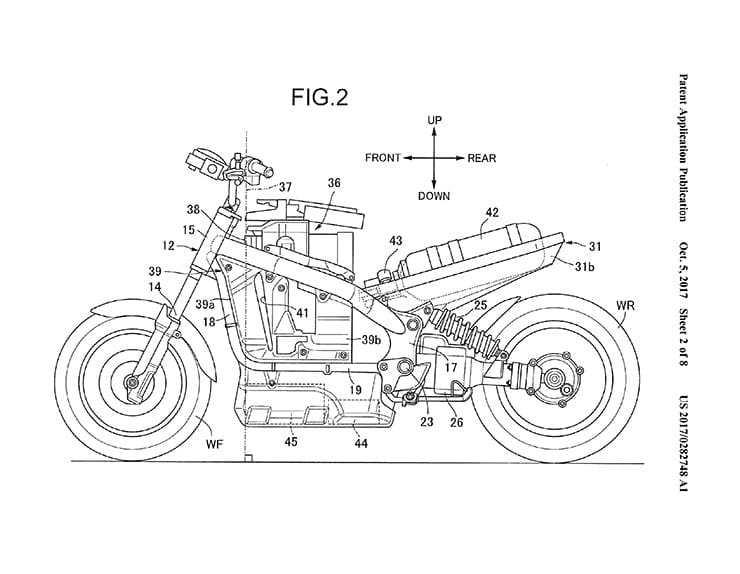

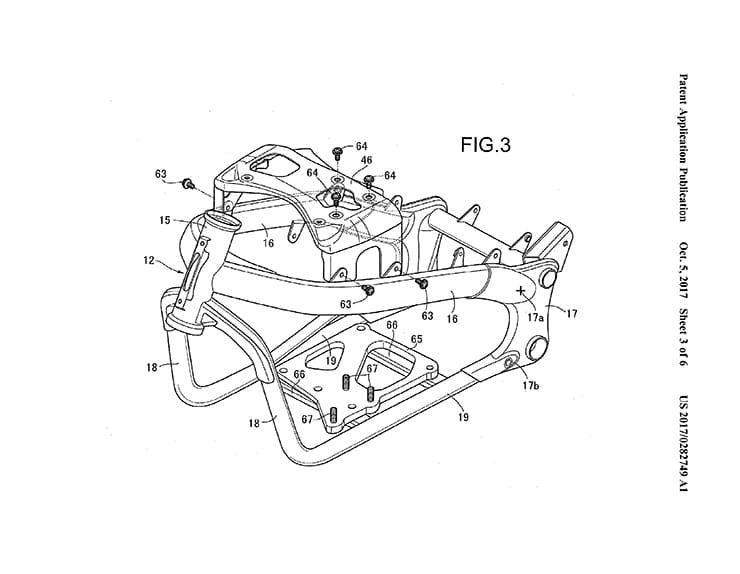

Let’s look at Honda’s new design first. It appears to be a small bike, around the size of an MSX125. There’s a pretty conventional perimeter frame and the high-tech hydrogen fuel cell fills the entire area that would normally be used for the fuel tank, airbox and engine. The bellypan contains an electric control unit and a small back-up battery.

The hydrogen tank is stuffed into the space under the seat, creating the bike’s odd-looking proportions by making the seat unit much fatter than you might expect. With no space remaining in the main part of the bike, the electric motor is integrated into the swingarm, driving the rear wheel via a short shaft. There’s no space for rising-rate suspension linkages or a conventionally-positioned monoshock, so the coil-over is simply bolted between the swingarm and the rear of the frame.

The fuel cell itself is a pretty clever thing. It uses a chemical reaction to combine hydrogen from the fuel tank with oxygen from the air, creating electricity in the process. The exhaust is pure H2O. Water.

The benefit over a battery is twofold. First, the hydrogen tank under the bike’s seat can be refilled quickly. Given that range-anxiety and slow recharging times are among the biggest things holding back battery-powered cars and bikes at the moment, that’s potentially a big win.

Second, the other chemical needed for the reaction – oxygen – is taken from the air, just as it is in a petrol-powered bike. A battery-powered machine has to carry all the chemicals needed for its electricity-generating reaction, which adds to the size and weight of batteries. In comparison, fuel cells can be relatively light, even though – as shown in these drawings – they’re not terribly small.

Hydrogen is also a potent gas. Once compressed, it can be used to pack a lot of power into a fairly small fuel tank. Like petrol, and unlike electricity, it can be transported in trucks or ships, so some argue that a hydrogen fuel station infrastructure would be easier to create than a network of fast-charging electric points able to deal with huge volumes of battery-powered vehicles.

It’s not all rainbows and unicorns, though. While hydrogen promises a lot, there are big hurdles to overcome before it stands a chance of replacing petrol or diesel in powering vehicles.

Despite the argument that it’s easy to store and transport, the gas is so thin that it’s actually very hard to contain. It either needs to be compressed at incredible pressure to get lots into a small volume, or it needs to be stored in liquid form at -253°C. Hydrogen molecules are also the smallest in the universe, making leak-proof containers hard to build. Hydrogen filling stations would, therefore, need to be completely reengineered compared to current petrol stations.

There’s also the issue of producing hydrogen in the first place. Most hydrogen is currently produced from hydrocarbon fuels, like natural gas, so carbon dioxide is still released into the atmosphere during the production process. The alternative is electrolysis, which uses electricity to split water into hydrogen and oxygen. That’s clean, but requires a huge amount of electricity, which in turn would need to be generated from a renewable source to give hydrogen fuel cells truly green credentials.